ANASTASIA SOLDANO

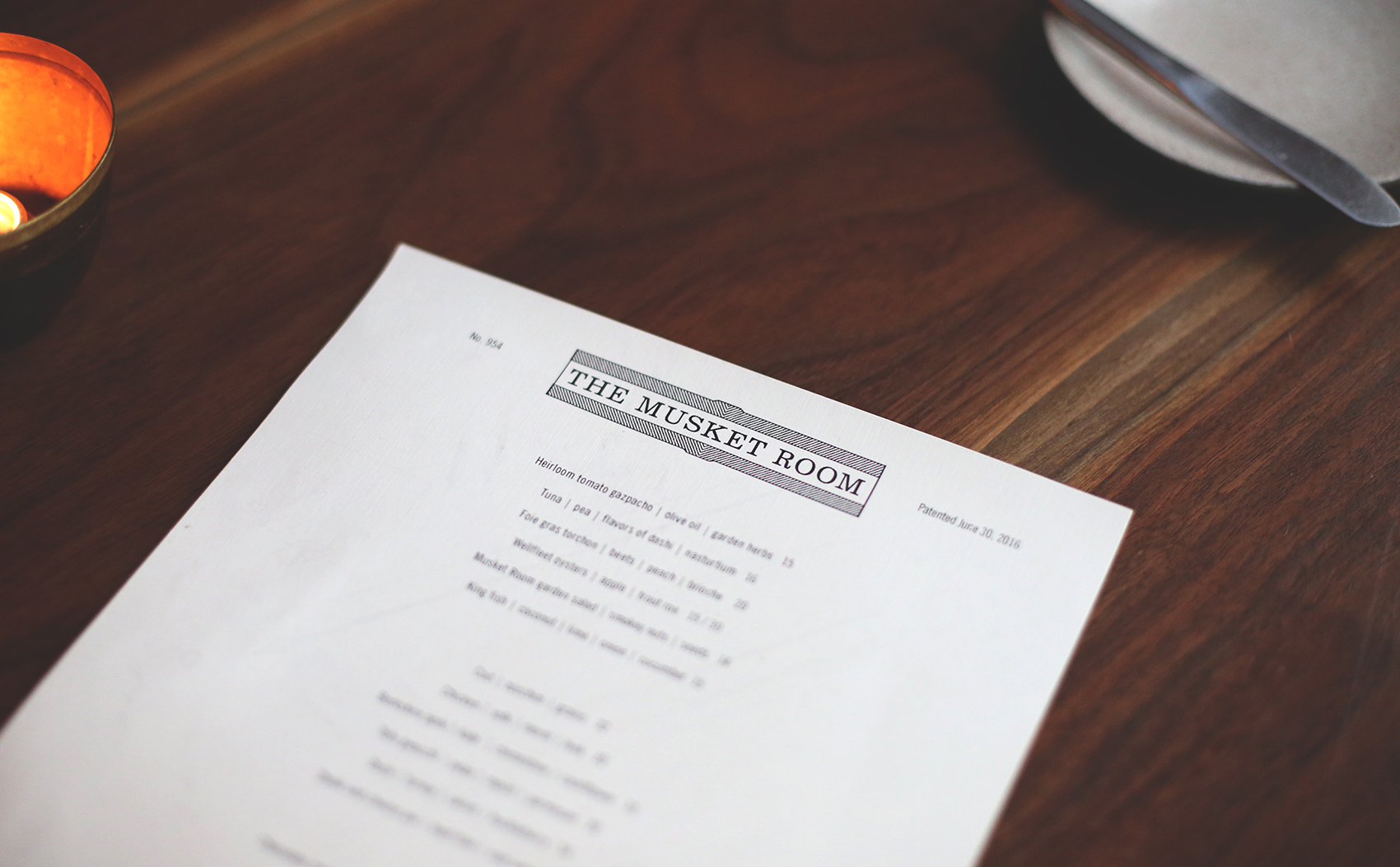

Assistant General Manager of New York City's The Musket Room, Anastasia Soldano talks seed-to-table dining, her journey from her large Russian-family dinner table to the halls of culinary arts school, and why she moved from the kitchen to the dining room, bringing her New Orleans style hospitality to this Michelin Award winning Nolita oasis.

Tracy: You are the assistant manager of the award-winning restaurant, The Musket Room which leads the industry in delicious local fare. What sparked your interest in food, and in particular the farm-to-table movement?

Anastasia: I first fell in love with food when I was about 5 years old. I was the kid who wanted to be a pizza maker and couldn’t stop telling everyone about it. So as soon as I was a teenager, I rode my bike down to the local pizzeria, got my first job, and fell in love with it right then and there. Aside from the food aspect, I’ve always been fascinated by the reaction people can have when they sit down and share a meal. That's rooted in being a kid as well because if I made a dish and you liked it? Well, that was it for me. Naturally, as an adult I expanded my idea of food being a career and went to pursue my Bachelor's degree at The Culinary Institute of America. And after working in some incredible kitchens, I soon fell in love with the Front of House. Coming from a position of a cook where you’re working 14, 15, 16 hours, I know that you don’t often get that incredible satisfaction of seeing someone's reaction to what you’ve just created. You've put your blood, sweat, and tears into it, and so it's something else to watch the reaction of your guest while they experience it. I knew that I wanted to have conversations about food with people who were as passionate about it as I was, and also to be the messenger for the amount of work that Chef [Matt Lambert] puts into each dish here.

In terms of farm-to-table movements, when I was a cook I had this light go off one day where I thought, "If I’m working this hard on something that someone else has already grown, what are they doing before it lands on our cutting board?" So I started going back. When I worked for Dan Barber a couple of years ago, I really grew into an under-standing that this wasn't just about being 'farm to table', in fact, it’s seed to table. It's about more than what you're going to add into each dish--it’s about the minerals in the soil that each vegetable was planted in as a seed. It's also about eating in moderation, and in variation: not going overboard on the newest superfood, or on only one type of meat. It’s about the beauty of being able to harvest everything we use in our kitchen. So as a chef, I began to ask, “What is the process of growing each item?” So today, I still have the daily objective of having that same fascinating dialogue that I too got to discover about where our food comes from, and to be able to tell our guests that story. You can still see the light go off in them when they begin to understand the concepts that my own mentor’s instilled in me. From chefs setting up their station a certain way, to where they draw inspiration from, to the hard work they put in every night, it all connects to this immediate sense of gratification: when it hits the pass and is off to a guest.

So for you, the front-of-house is where you get to tell that story, to make sure diners get to discover what has gone into each dish. You also paired some wonderful cocktails with the dishes I ordered when I first came in this year. Is that something else you've learned a lot about?

Yes, I enjoy being that voice for the cooks, but also for the cocktail managers if our guest is at a table rather than the bar. They both rarely get the chance to lift their heads up from what they're doing to come over and explain why they chose a certain garnish from our garden, or why something is more flavourful in each particular season. It’s an amazing feeling to be able to communicate with a guest about our menu, all the way from describing the importance of the soil each zucchini came from, to the exact way that we place each item down on the plate, to the moment I’m putting the dish down in front of them. The experience is in all of it. Then to your point of being able to go a step beyond the dish and talk about wine, beer, or our seasonal cocktail feature, and how those play into their meals.

Something really unique about New York is that, while yes there’s this big, global movement that’s been going on for a while now thanks to Alice Waters (who I thank tremendously for doing what she’s done to explode the farm to table movement), but the neat thing about New York is that when you think about it, you just think of a city - a concrete jungle. But we have so many permaculture focused gardens, and we have really cool new breweries and distilleries. We carry King’s County here which is made in Brooklyn. There’s Owney's NYC Rum, who make Rum just off the Grand Stop on the L-train. Everyone’s really putting their heart and soul into creating truly local additions to the art piece of this local food movement. So leaving the kitchen was one of the saddest things I’ve ever done; it’s amazing to be back there holding something that's still dirty from the farm, then turning it into something so vibrant and put-together on a plate. It's really a process of creating art. But working Front of House, you get to bring someone else's creation to people, knowing the entire process. Then getting to pair it with a glass of wine knowing that those farmers put that same care into harvesting each row of grapes, and their whole process of getting it from seed to bottle. It's all those little details that no one immediately thinks about, like the gin that goes into your martini and how that particular juniper in it was grown. For us it’s also cool because we have our garden back there, so we can use our own spring peas, blueberries, mint leaves--even or own tomatoes go into our cocktail program. And I get to make sure that story gets told to our guests.

Clearly consumers understand the importance of having our food come from as close as possible, but yours comes from just right there. It's as close to freshly-picked as you can get. You can see plants growing from most of your dining room tables.

Yes it's quite beautiful. We also use that space to bring our guests out to meet Chef [Matt Lambert]. We really encourage our chefs to come up and meet the guests. So with our outdoor space we’ll offer intimate garden tours, or they’ll do a course outside with Chef--and not just Matt, but the sous-chefs as well. They’ll cook some oysters, or share some tar-tar, or they’ll have a craft beer that has been made within the Northeast area, or they’ll make a punch that consists of items from the garden. That way the Back of House also get to take a break from the kitchen and come out to see their guests. They get to have that ah-ha! moment where they watch the guest taste freshly picked ingredients, or hear that the tomatoes in their dish were this freshly picked. It’s a more interactive way to dine and expands the experience beyond the table they're sitting at.

To your point of realizing that not only is it your own work cooking the vegetable, but also the work the farmer put into that vegetable--ensuring the soil it grew in was full of minerals. Understanding that has made me willing to spend more on my meals. We're not just paying the restaurant, our dollar is actually contributing to the economy of the smaller, hardworking farmer, the local, artisan bread baker, the gin distillery--all who put that much more care, time, and passion into their product. There are no cheap, fructose cocktail syrups, or sauces that sit on shelves forever. Rather, you're voting with your dollar. You’re saying, “I want more of this in my community and around the world”.

That’s a great way of putting it. These dishes are creating a whole economy here. It’s crucial to a better way forward. I think there’s an extreme importance to consumers being aware and then being responsible. I hate to sound cliché but when people watched Fed Up, it said something. When people read Dan Barber’s The Third Plate, it says something. When people read The Art of Simple Food by Alice Waters, it says something. We're moving toward a way of eating where we're taking an animal and using the whole thing--nose-to-tail cooking. The amount of time and energy it takes just to raise one animal, it should make no sense to dice it up and only send out the perfect looking pieces. What did that animal really live for at that point? And we'll have to raise many more of them if we're going to continue to eat that way, which of course adds to pollution and all these other repercussions. I can't stress the importance enough that people are conscious of what they eat, how they eat, and how much they eat. One of the reasons I’m here at The Musket Room, is because I fell in love with Matt’s food when they first opened. His whole kitchen pays so much attention to all of these things, yet the food is the best you've even tasted. If we keep consuming food the way the majority of America is, we’re going to cause irreversible damage--if we haven't already. It seems like such a small ask of people to just think about what they’re eating. But if people can't for whatever - often legitimate - reasons, places like ours are able to do it for you while also offering something you’ve never tasted before.

So yes, I certainly agree that if people are spending their money wisely and on the right people who are considering the best farming processes, it's going to have a very positive effect - one which we're already starting to see. In Spain, there’s a biologist by the name of Miguel Medialdea who runs Veta La Palma where they technically 'farm' freshwater fish. The fish exist in this natural, sustainable 'aqua-culture' marsh that is essentially filtering the ocean because it's the cleanest it’s ever been due to the algae ecosystem there. So you’re getting this fish that’s typically a bottom-feeder "garbage fish" if you buy it here, but it tastes amazing because of where it grew. So sourcing that way where it’s responsible, innovative, and where they’re cultivating things with careful consideration to natural ecosystems, matters. But it also only matters if our consumers are doing it with us. We can only do so much; the next step has to be people coming in the door, and not only sitting down and dining with us, but also listening to that story and taking it home with them.

Going back to why we love what we do, is that we get to tell these stories to our customers because we’re friends with our farmers. We know them - we go to their farms, and they come here to drop off produce. And that's a plus as well because sometimes they’ll have extra branches off their trees with cotton balls or blossoms on them, and so instead of ordering flowers that week, we get to have something from the farm. For them, it’s not going to waste, and we all partake in this because this is our culture, and these are our friends. New York is a city full of transplants. Neither you or I are from here, so what can we do other than continue to support each other. These are the people that we'll possibly be spending the holidays with when we can't go home - it's a community that makes New York what it is.

You were born in Los Angeles, so let's talk about California vs NYC. People have the idea that California has the best produce, but an interesting part of reading The Third Plate, was when Barber wrote about carrots. They actually grow better in colder climates - the winter temperature brings out that specific sweet taste?

Yes and without hearing or reading that, you wouldn’t know, which is where I get to tell our diners exactly why the carrots in our dish are bursting with flavour. The other thing to consider when looking at this idea of the ‘best’ produce coming from California is the size of it. It’s got the most produce, so of course it’s always going to be a machine. The importance for me when sourcing locally is understanding the landscape of the State of New York. I can say, “Okay I’m not going to eat as much California meat because I watched something on it, or my friends told me not to, or because I’m doing this X, Y, Z diet.” Well that’s fine and that’s your choice. I don’t eat a lot of that meat, but I do enjoy it sometimes. But there’s a step beyond that, it’s not about eating only vegetables, it's about knowing how those vegetables grow. Dan [Barber] was the main reason I jumped in my car after college and drove all the way to Up-State New York to work on his farm [Blue Hill at Stone Barns]. And he talks often about the importance of rotating your crops. There are certain vegetables you can plant that take nutrients away from the soil, and there are some that you can rotate in to add those nutrients back into the soil. Dan does this fantastic "rotating risotto" where he’s constantly changing the grains because the next thing he grows for it is actually pumping nutrients back. So staying local yes, you’re not transporting food across the country, and if you’re going local by shopping at the Farmer’s Markets, then you're going that extra step beyond, and you get to know your farmers. If you don't have the time for the Farmer's Market, or to cook at home for whatever reason, you can get to know all of these so-called 'farm-to-table' restaurants in your area - because they know the farmers. You get to find out from them what their farmers have growing, why they’re growing it, and what's the most flavorful dish of the season. And you’re also helping them turn their land for the next process, and the next season.

There are so many catchphrases like 'organic', 'vegan', 'gluten-free', 'non-GMO', which of course all come meaningful places. Yet, what you said about "getting to know your farmers" is more important than these labels. To find out from farmers what organic means beyond the label, or why more people are being affected by gluten. Many still think it's frivolous or a rip-off to buy these things, but if we consider ideas like why we should avoid monoculture crops, it goes beyond the frivolous or pretentious.

Yes. When it comes to these labels or telling people, “eat organic,” or “don’t eat processed foods," or "Only using Anson Mills’ grain," that’s all fine and good because yes, there is a company that’s trying to do better by their consumer. But what good are you doing if you’re getting an organic something at the superstore from some country or place you’ve never been to, when you could walk the three or four extra blocks to the Farmer’s Market and get something that's also local and much more likely to be in season. Seasonality is also a big factor in how our food tastes as well. So if you’re actually paying attention to what you’re eating, where it's coming from, how it's grown, you get to understand your food beyond the organic or gluten-free label. It goes back to what I was saying before with moderation. Finding out from farmers how long something is in season for, or what it takes to grow it, also helps you begin to eat in moderation too. You savour things and appreciate them more.

I’m drawn to restaurants like this where first of all, on a plate it’s stunning, but it's also not a massive bowl of quinoa and beans. It’s delicate but I always leave full. Is this because there is so much more in terms of the flavours added? From truffle sauces, to pea pure, to beef jus, and nasturtium garnishes. Do these add to feeling satiated rather than simply stuffed?

That’s a really important piece and an important thing to discuss. It’s something that Matt and I often talk about, where if someone looks at their plate and doesn’t feel like there’s enough food - aside from wanting to make it clear that we’re here and happy to feed you more - but often we think about what our society's definition of 'full' is. Matt is not a waif man by any means, but his, my, and your definition of full seems to be in the same realm. When do you feel satisfied? For us and others in the industry, being full is not about reaching a gut-busting point where you can’t breathe, just to feel that you’ve got your money’s worth. Rather, it’s the experience of each flavor and how they interact with one another course by course. And certainly, you shouldn’t be leaving the restaurant with your stomach still rumbling because if you did, then we really did something wrong. But if as an American culture, we’re getting used to that sick-to-your-stomach feeling of having overeaten, it would make sense for us to move beyond that. Going back to moderation, a great dish is not about the quantity in which you’ve eaten every helping, it’s actually about breaking down how many different things have gone into each dish to make every portion more satisfying. Personally I’m not sensitive to much, but I do know that if the amount of meat and dairy that I’m including in my meals is too large, or if I’m eating meat three or four meals in a row, it's likely that I'm not going to feel too great. So here at the restaurant, we break it up with so many more additions to your plate. You don't feel like something’s missing, and there are many courses to give that variation.

Our parents' generation was the first to be mass-marketed to with processed, grab-and-go foods, and it's their kids who are really starting to take it back to the basics. Jon Stewart once said that, "The pendulum can only swing so far in one direction before it has got to swing back." I think that applies to food as well.

It’s definitely true, and another thing worth looking at is how only a few generations ago everyone had it nailed into them to eat as much as you could when food was on the table, because everyone had just gone through wars and there was a lot scarcity. My family is from Russia, and we often hear, “Poor girl, eat more! You’re skin and bones!” So it was probably difficult for my grandmother to watch me put my plate away when I was full, but my parents knew I was healthy.

But to your point on how we grew up in this generation of food where that over-processed, pump-it-out, on-the-go type of food really took off. It was commercialized to a degree that had never been seen before when we were just babies. Luckily for me, while sure we had some of it in my house, I still grew up with my great grandparents who made food over all day and would drop it off at our houses. So just as readily available as a bag of chips, we had cut-up fruit, cheese, and meats. There were always pelmeni, and blini’s in the fridge ready to eat. Just as I didn't learn english as my first language, I didn’t learn about all of this other food until I started going to school. Not to say that America is terrible for introducing these things, but they were definitely at the forefront of making processed food. Of course there's reason for this food coming onto the market - my parents, just like many others, weren’t going to cater to a 6-year old and feed me at every moment I demanded to be fed, but I quickly learned that there were windows of opportunity for home-made food that I wanted to eat.

You brought up your grandparents and great-grandparents. Another important part of life that we seem to have lost, is intergenerational dialogue. I've often sat at restaurants and met someone who’s 20, 30, or 40 years my senior, but we still share the same love for food: it spans generations and brings all ages together. Do you think this is another part of the reason you're here?

Yes absolutely. I grew up in a large yet tight-knit family. My ancestors ran from Russia during the Russian-Afghanistan war as refugees - they were lucky to be here. Actually they wound up in Cleveland, Ohio of all places. But from a very young age I was fortunate to have my great-grandparents who were around until I was into my teenage years. They passed when I was about 13 or 14. So I could look down the table and there wasn't just two or three generations, there were four generations of our family sitting there. Being a Russian family, the men were always in the corner salting and drying out fish, drinking vodka, and all the women were in the kitchen, chatting away, cooking the potatoes. Both sides enjoyed their roles, and the kids were given their own role of setting the table, so everyone really felt a part of dinner time. We would sit down and everyone had played a part in that food being on the table--mind you the grandmothers would always get up in the middle of everyone eating and make sure no one still needed anything, and that everything was still hot and full.

I feel that this doesn’t happen often enough anymore for many families, and if it does, people are often still disconnected using their phones or the like. So when I see our regulars and other families bringing in their grandparents it just reminds me of that important part of my upbringing. If we could all take the time to have a real meal, with real connection--not just in front of the TV--then people’s diets might be better, and people would be more connected to their families, and their elders.

To your point on food spanning generations, it couldn't be more true. Life really began to speed up around the late '90s - we became this fast paced culture, not only in New York but everywhere. I think that’s where food fell by the wayside. Food still spans across your and my generation because we sat with our parents at dinner, but I think somewhere along the line, food got lost for some parents. So when you sit down and there’s that 60 or 70 year old next to you, they were cooking for most of their lives, so you likely have that same love for slow-cooked food. It may be the generation between you two that didn’t get that same enjoyment of slow mealtimes.

I also want to talk about presentation. For anyone who enjoys Chef’s Table, or who can see the amount of innovation and care top chefs put into each dish, they'd still be floored by everything that comes out of your kitchen. It has the power to surrender one into a state of awe. It's those rich, life moments when we’re enchanted by what's in front of us. You don’t just scarf it down, you stop and appreciate every angle of the dish. Having been a cook, you certainly have the duty to create flavourful food, but do you consider it creating Art as well?

Yes, you’re absolutely right. As a chef, you are an artist. There’s something that holds truth to the fact that it is called culinary arts. Another reason why I fell in love with Matt’s food years ago is because there's heart to it that you can see. We’ve been talking about how food is a story, but for us we have nothing without it. I don't know what I would be doing if I wasn't in the food industry. So the nice thing is when Matt comes to line up every shift, and he tells us about a new dish that’s coming out, or the story behind it, a lot of the times it has to do with his family, or his childhood. Something as simple as the construction of a traditional steak and cheese pie - he’ll put his own spin on it. In New Zealand, it’s this quick, pick-up thing, whereas here he’s taken all of his favourite parts, but he wants to let them show.

It’s really easy to make food, but it’s another thing to turn it into art. So being able to sit down and see that unfold in front of your eyes, is one of the reasons why I fell in love with the food here. It's a full story going back to Matt’s childhood and the way he was raised, paired with all of our journeys learning the history of farmers and farming. There’s so much to discover, and it’s our job to tell you guys about it. The more you know about our story, the better.

It’s not just food, it’s not just art, it's almost another form of entertainment; a way to better invest your time.

This is something we talk with our staff about often. It’s never going to be easy to keep a restaurant going, ever. If you want to break it down into black and white, restaurants serve food, so if you have good food, people will come. That might be your easiest way of having a restaurant: having great food and letting nothing else matter. But the way you get your regulars to come back, and the way you meet friends, stems from something more than just food. Some of my best friends are regulars from New Orleans, and Cleveland. Those are the people whose weddings I’m now in, or who made me the god-mother of their kids, because we connected. You don’t need to learn everyone’s favourite color or zodiac sign, but chances are you have something in common. I often say, "We creep because we care".

Once I heard a guest mention Frank Lloyd Wright, and since my family has one of his homes in Staten Island and they were looking for directions over there, we chatted about that. It's the simple things that we’re here for - giving someone directions or local knowledge. It's about connecting with that next person so that when they come back, they’re not just coming back for Matt’s new creations, they’re coming back for you as well. Sometimes people are visiting and wondering what other places to have a drink at, and we won’t shy away from giving them suggestions for places that are similar to this one in terms of their cocktail menu. We’re in the industry so we’re always eating and drinking; it takes no time to put a list together for them. It’s just one more level of connection that we can very easily add. Living in New Orleans gave me a lot of that mindset. I don’t have to be a clown about it and I certainly don’t want to preach unnatural hospitality on others, or suggest that we have to roll out a red carpet for everyone we meet, but we can all make these small gestures even just in our daily lives on our city streets.

Just giving someone a smile, or sharing a chat in the elevator, you’ll instantly lift the overall mood - if it's coming from a genuine place. The social sciences have concluded that the number one determinant of happiness is not wealth, fame, or material gains, but it’s those pleasant moments of feeling connected to one another.

Yes, I actually just had that happen on a flight back from Miami. I was exhausted, and what should have been a two hour flight back to New York wound up taking 12 hours. I became friends with the guy who was sitting beside me, and since then we've gone out for drinks. He’s a finance guy who grew up upstate, and he was trying to figure out how to save his friends farm, so naturally we started talking about food. So rather than getting frustrated about this major flight delay, I wound up getting to know a new friend. Often these interactions can open your mind to new dialogue - especially if they’re in a different generation than you. So yes I agree, it’s very important to connect with each other, because so much can disconnect us if we don’t build the habit of getting out of our thoughts. We have people around us all the time, but we could wind up without conversation any of the time. Which is another reason why I love my job, it keeps you out of that habit and brings new people into my life constantly which is likely what I knew I wanted to be doing right from being that small girl who wanted to be a pizza maker.

A perfect point to end on. Thank you for your insight Anastasia, and I look forward to bringing my friends into The Musket Room soon!

Capture Queue is a one woman team, so if you notice any typos or errors please don't hesitate to send me a message here.